Little Whale

The Last Son Sent to War

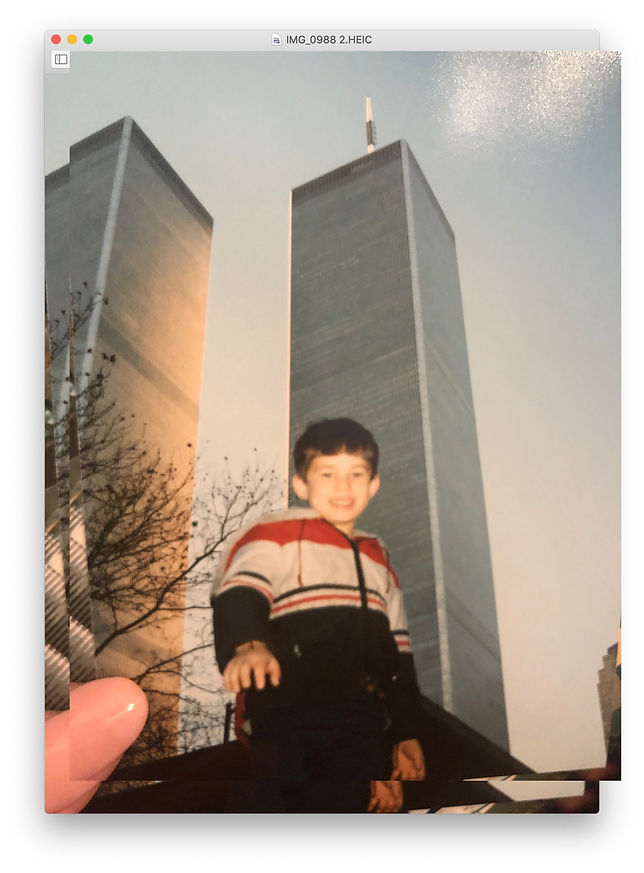

In the first photograph, Robert is smiling down at the camera with the Twin Towers standing behind him like two, giant silver Cuisenaire rods. My father must be kneeling to take the picture from below or perhaps my brother has hopped onto an unseen bench cropped from the photo. His jet-black hair is shaped in a bowl cut and he is wearing a red and white coat with no logo, most likely from the Caldor outlet in Bristol, the town next door. From that part of central Connecticut, it is a two-hour trek to New York, the first leg a 45-minute drive to the train station in Bridgeport followed by an hour-long Metro-North ride into the city.

I can picture the scene that morning: my twin sister and I grumbling, jealous we would not get to ride the train.

“But, Mommy, it’s not fair!” I can hear myself whine as she works the brush through my snarls.

“Oh, Sweetie, you’ll get to go some other time,” she would have insisted as she pulled my hair into a ponytail with one hand and used the other to fasten it with the elastic of those finicky, marble-ball hair ties. I can see the scowl on my face and my quivering lip as I watch the car back down the driveway.

She must have told him how upset we were. It is but two months later, on our ninth birthday, that my father is helping Maggie and I with the zippers on our puffy winter coats before loading us into the family station wagon. Faded white zippers on coats with colors I cannot recall. I should be able to summon every last detail of a trip I had once so coveted, but most of that memory has blended into a blur of Manhattan in midwinter: snowy sidewalks, muddy slush in the streets, exhaust fumes rising through the chorus of car horns.

I cry all the way up the Statue of Liberty, I remember that part. My fear of heights taunting me with each step. “You could slip through that gap under the stair and fall all the way down,” the invisible voice warns. My eyes widen. I freeze.

“Keep moving. You’re okay,” my father coaxes as I grip the railing of the spiral staircase. I move ahead at a snail’s pace. Every step a soft, deliberate press into the heel of my winter boot as if Mother Earth might notice a human’s devotion to her almighty power and take pity–bless them with an immunity to gravity. It is New York, after all. Wouldn’t anything be possible?

I close my eyes–not tightly, just slowly and with intention, like I have seen my father do when the Righteous Brothers come on the radio. I try to channel that invisible resolve I know to be sewn into the strands of my own twisted ladders, DNA forged by the fearlessness of a night nurse and a Navy corpsman.

Still, I am not sure why “Doc” thought this was a good idea. I have always been afraid of open stairs. Like the shaky ones leading up to roller coasters or water slides at the amusement park. The ones I manage to get halfway up before turning around, scrambling down, and settling for a low-stakes ride on the spinning teacups instead. Maybe he does not understand that getting too high off the ground makes me dizzy. Like being turned upside down. Like my stomach is floating up through my throat and cutting off my ability to breathe. Like I am about to black out and come face to face with some vast unknown.

Impatient families squeeze past the three of us, giggling at my tear-soaked cheeks as I tip-toe along, mortified and wholly unconcerned with what the statue has to offer in terms of scenic views or symbolic hopes for humanity. I just want out. I want to get down. Back to the base with the engraved bronze that I imagine now reads, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses and your sniffling daughters clinging to the promise of a Happy Meal after the ferry ride back to Manhattan.”

*****

There weren’t any benches outside the McDonald’s in Midtown but my father did manage to find a low cement wall where we could sit and have our lunch. We had planned to eat inside the dining room–out of the cold–but a woman in the next booth was talking to herself while staring at Maggie so we gathered our food and shuffled outside. The next bit I remember was shivering while chewing on a chicken nugget, hot steam rising off the oily crust into the chilly air while I studied the face of a man on the Calvin Klein billboard above us. I wondered why he looked so angry in his underwear seeing as how he had a lot of muscles and, I presumed, a lot of money, but curiosity waned as my focus shifted to picking crispy bits of overdone French fries from the creases of my paper bag, washing them down with eager sips of Diet Coke.

Once our three straws were slurping in unison, we stuffed our cups into an overflowing trash can and started walking towards the subway entrance down the block. We could not have been more than a few feet away from the stairs when my father went down. I do not remember seeing him slip on the ice, but I do remember the look in his eyes as he started to fall. Even now I hate replaying the scene in my mind, turning in a panic as questions raced through my head: What is that terror in his eyes? How do I make it stop?

“Daddy! Are you okay!?” I cried out as Maggie bent to grab his hand.

“I’m fine, I’m fine,” he mumbled, waving off our palms.s

He rolled to his side and pushed himself up, wincing in pain. He had slipped and fallen backwards the way a cartoon character does, his legs doing circles in the air right before dropping onto the pavement, back-first followed by a THUNK of the head, cushioned only by the cheap knitting of a brown, winter beanie.

He readjusted the hat while Maggie and I smoothed his coat hem with our mittens. When we reached the station, we took the stairs slowly, my father leaning in a way that did not hurt while stepping down. I couldn’t help but notice that even in pain his movements were less dramatic than mine on our descent from Lady Liberty’s crown. Still, our slowed pace was not without consequence. By the time we caught the subway and arrived at Grand Central Station the train back to Connecticut was already leaving the platform.

“Dammit to hell!” my father hissed under his breath as the last of the train cars rolled by. My sister’s eyes met mine without either of us moving our heads. There was the dammit to hell Dad used when he stubbed his toe or dropped a tool while fixing something. That was the kind of dammit to hell you could secretly turn to your siblings and laugh about. This dammit to hell was different, though. I slowly looked up and tried to read between the lines of his forehead wrinkles shifting as he grimaced.

“Will we be OK, Daddy?” I asked.

“Yes, Sweetie,” he chuckled, “Everything’s going to be alright.” He pointed to the phone booths in the corner of the terminal. “Let’s go call your mother. Let her know we’re running late.”

We spent the next hour killing time waiting for the evening train. We walked the few blocks to Times Square. Stared at the lights. At the neon signs. At the flow of pedestrians queuing up at street corners before spilling into crosswalks like ants pouring out of an anthill. On the way back to the station we noticed a crowd milling in a wide alleyway and decided to see what they were staring up at.

It turned out to be a fire on the upper floors of a small building. I don’t recall much from this detour but I remember the charred facade of the top floor. I remember dark smoke rising around the stream of water from a fire hose. I remember black bricks climbing into the white wall of an overcast sky. I remember asking my father questions.

“Why did it catch on fire?”

“I don’t know, Honey.”

“Why aren’t there more fire trucks?” I persisted. “Why aren’t there more hoses?

“I don’t know, Honey,” he said again, this time slowly and with intention.

I took the hint and zipped my mouth shut but the questions swam around inside me like a school of fish darting between the walls of my stomach. I hated that feeling. I needed answers. I needed to know why. It was my signature question after all. How I had come to earn the nickname Beaker at home. Just like the lab assistant on The Muppets who only made one sound: a series of squeaky, staccato chirps while trying unsuccessfully, and incoherently, to steer his careless boss away from mishaps.

My parents would fondly tease me when I started bombarding them with my Why-based line of questioning. “Here comes Beaker! Why, why, why?! Meep, meep, meep!” they would screech, laughing hysterically as they performed the high-pitched impersonation. If I was in a sour mood, I would stomp out of the room in protest. If I was in a good mood, I could roll my eyes and smile at my own ridiculousness.

Looking at the pictures now, I wonder what types of questions my brother bothered my father with when they were in the city. In the second photograph he is no longer outside the World Trade Center but up in the observation deck at the top of one of the towers. He is holding the railing of a floor-to-ceiling window with his left hand and looking back over his right shoulder toward the camera. That arm is outstretched, hand upturned like he is posing a question. The city fills the window behind him, building blocks stacked and staggered like some endless, gray Legoland. He is curious about something out there, his mouth slightly ajar, looking at my father as if asking, “How high up are we?” Or maybe, “When do we get to go to McDonald’s?”

Perhaps I do not know the question he is asking my father but I am sure he is not wondering why the buildings in his world are fractured or fallen. Or who broke them. Or why he has to leave the one he grew up in. Why he cannot take his favorite toy. Why his mother is gone. Why he cannot make her come back to life. Why such a nightmare is even unfolding.

In the third picture he is turned to the window looking into the expanse of 100 stories below. Outside the glass, the top of the other tower is gleaming in the sunset. Steel beams reflecting sun beams like strands of tinsel. I squint, looking into the black windows nestled between the golden rods. Like peeking into the mystery-filled windows of an abandoned house before it is abandoned, curious about the lives of the ghosts before they become ghosts. I want to warn them but I cannot. And so, I am relieved I cannot see them from here.

Naturally, one's eyes follow the vertical window lines down the photograph to where they meet the back of my brother's coat and its fuzzy, gray hood. The kind of hood that unzips down the middle into two winged halves that look like a whale's split-fin tail. This time both of his palms are turned up, resting against the railing as he stands on his tip toes and strains to understand the vastness of the world over the muffled sounds of the city beneath him.

“Is it all real?” Or am I imagining it?” he might be wondering, peering down like he wants to dive into the sea of skyscrapers, to explore the waters of glass walls, to swim between the buildings or to soar like Superman–his coat a magical cape that floats him high above the rooftops, not like business suits and blazers that flap furiously in fall winds.

Perhaps I do not know quite what he is asking himself, but I am sure he is not wondering about boxcutters. Or unmanned drones. Or civilian casualties. Or soldier suicides. I do not want him to know of these things. I do not want to place those answers into his curious little palms. He would have to ask me “Why?” and I would have to say, “I don’t know, Honey.”

I still have so many questions about the three pictures but I do not bother my mother. She has been gracious enough to provide me answers without my usual pestering. She sees me stumble on the photographs earlier in the day. I am visiting her two years after Dad passes away from cancer. From the tumor that grew into his throat and cut off his ability to breathe. Exposure to chemicals in the drinking water. Exposure to memories in the ether. I am flipping through old photo albums. The kind with the clear, sticky sheets so aged that if you peel back their yellowed edges to retrieve a picture the plastic disintegrates under your fingertips.

“You know, your father did not mean to take your brother there that day,” she informs me.

“To New York?” I ask, shaking my head.

“No. I mean to the towers,” she says, “They weren’t supposed to go there. Your father wanted to take Robert into the United Nations, but it was closed. It was a Sunday.”

She explains that when Operation Desert Storm began in 1991 my father was glued to the TV. Devastated. He had spent two decades trying to rebuild his life after Vietnam. Grieving the friends he lost there. Grieving those who made it out alive only to succumb to invisible wounds in the years that followed. His were hidden like that, too, appearing only as calendar reminders scribbled in pencil for monthly appointments at the VA.

When I was little, I stumbled upon some old Polaroids of him with friends in matching green t-shirts and cargo pants. He sat me down and told me stories of boot camp. Of long, hot ruck marches and of short, cold showers. Of how important it is to keep your feet dry on patrol. Of how he adopted two street dogs when he got to his assigned village in Vietnam. Of how Cleo and Huxley went missing one day and never came back. Of how he did not ask the starving villagers too many questions about it. He told me how his nickname was “Doc” and how that meant he had to take good care of his platoon and good care of the people in the village.

I noticed the way he did not talk about the other men in green t-shirts. The way he carefully avoided that and skipped straight to the end of his tour in 1971. How relieved he was to come home. How scared he was to turn on the interior car light at night when he first got back. He laughed at that memory but his face grew serious when he waded into the bit about getting tossed in the brig for refusing to go back to Vietnam. At one point, he stopped himself abruptly, choking back tears as if he had forgotten how much he hated that part of the story until he was caught in the middle of telling it, facing the ambush alone.

“What’s the brig?” I asked, hoping to break the tension.

“I can’t talk about that, Honey,” he whispered, his voice shaking as he told me to go watch TV in the other room and softly closed his bedroom door behind me. The only time his eyes looked like that again were years later when he touched the wall of names in Washington D.C.

I look down at the photos one last time, running my index finger over the plastic that has for decades kept safe the three images of my brother while so much else slipped away. The towers. The whale jacket. My father. Some of it lost in natural ways. Some if it lost in very unnatural ways. And I finally understand why he took his eldest son, his namesake, to New York that weekend. Why the day after he saw young soldiers filing into cargo planes on TV, he felt the urgency to throw my brother in the car as fast as he could, head down to the city, march him right up to the stone wall outside the UN and read that set of engraved words aloud to his little boy:

“...they shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks: Nations shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

My index finger guides the album cover closed as I bat my eyelashes in a foolish attempt to dissolve the tears into thin air, into the ether where they can settle soundless among the rest of the stories untold. Unoffered. Laid to rest, like the wish of every father that his be the last generation sent to war. The last to trade smiles and bowl cuts for green t-shirts and buzz cuts. The last to close its eyes and stare into the vastness of the world’s muffled horrors. The last to wish it unreal, unknown, as if they had only imagined it.